January 23 is the birthday of Ed Roberts, lovingly and respectfully remembered as “the Father of the Independent Living Movement.” It is celebrated annually as “Ed Roberts Day.”

In 1953, at the age of 14, Ed Roberts and his entire family contracted polio. Over the following months, as his family got better, losing all of the effects of the disease, Ed’s situation went in a different direction. For him, to stay alive meant spending his days using an iron lung, a large tubular machine designed to help his paralyzed lungs and diaphragm do their job.

Early on, he overheard doctors telling his mother, “Hope for him to die, for, if he lives, he will be a vegetable.” Later, recounting this, Ed would decide, “If I am to be a vegetable, I decide which vegetable and I choose Artichoke because they are prickly on the outside but have big hearts on the inside.”

There was a time at home when, tired of the struggle and lack of power and control over his life, he did want to die. He stopped eating. Though they force fed him, he lost 57 pounds. The day the last nurse gave up and left, he decided he wanted to live. With the medical professionals out, he took control of his life and, with the help of his family, began to thrive. He went back to school, first by phone and then by attending. The first day attending – his Senior year – stuck in his mind and changed everything.

“I remember that day very clearly. I arrived during lunch time. My brother lowered me out of the back of the station wagon, and it was like a tennis match – everyone turned to look at me. I looked at someone, right in the eyes, and they turned and looked away.

That was when I realized that maybe it wasn’t my problem; maybe it was their problem. I checked myself out, and I realized two things. First, their looking at me didn’t hurt, physically; and, secondly, I realized, hey, this is kind of like being a star – and I’ve been a star ever since.”

Besides his decision to die and then live, Ed’s first fight for his rights as a disabled person was for his high school diploma. The principal had said no diploma due to not taking and completing Physical Education or Driver’s Ed. Both of his parents were labor activists. They showed him the ins and outs of protesting. He and his mother, Zona, went to the school board and pled their case. He got his diploma.

In 1962, wanting to study political science, he was told by his counselor at the community college he was attending, Jean Wirth – a woman and friend who would come back into his advocational life later – he should consider going to University of California at Berkeley. When he went to the Rehabilitation Services Commission for financial support under their Vocational Rehabilitation program, he was tested and told, “Well, this test shows that … you’re very aggressive.” The counselor had said it as if it were some kind of negative thing. “Well, if you were paralyzed from the neck down, don’t you think that aggressiveness would be an asset?” Ed was told it was unfeasible for him to ever work. (Ironically, thirteen years later, in 1975, Governor Jerry Brown would hire Ed Roberts to be the Director of the Rehabilitation Services Commission for all of California – in essence, the boss of the guy who had told him he would never be able to work. It was a position he would hold for nine years.)

In 1962, at University of California at Berkeley, the attitudes were very similar to those of his counselor. He was told by administration that “they had tried cripples and it didn’t work.” Ed sued to be allowed admission and won, and the semester he started at UCB was the same semester James Meredith would become the first Black man to attend all-white University of Mississippi. It would be one of many correlations between the Civil Rights movement and the Disability Rights movement.

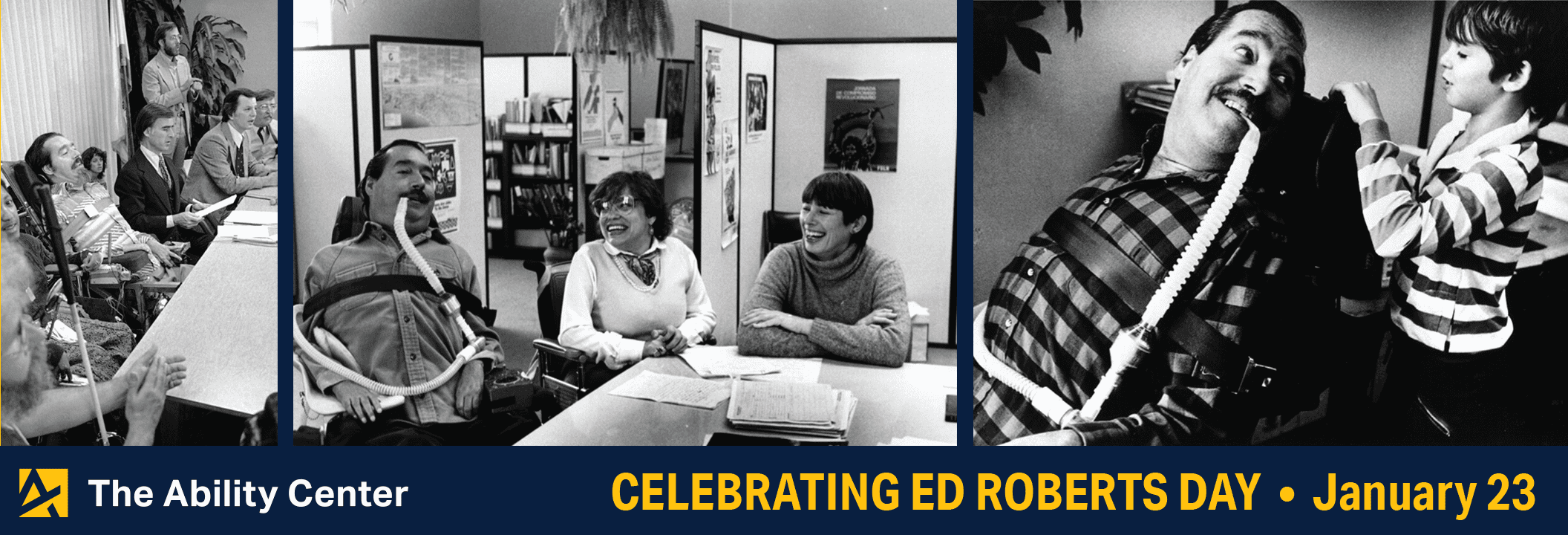

Ever the pioneer and advocate, Ed helped others with significant disabilities attend Berkeley. Calling themselves “The Rolling Quads” and unable to live in inaccessible dorms, the group set up their own “dormitory” in an unused ward at Cowell Hospital on the edge of campus. It needed to be a place capable of housing an 800lb iron lung, after all.

The 60s were a time of protest and great change, especially for students on college campuses. Ed learned a great deal from the protests and fighting for one’s rights, especially from the women’s movement – they were the first to see a connection between struggles – the “shared oppression.”

He reconnected with Jean Wirth, his old counselor and friend, helping her with a grant that ultimately created funding to begin the Physically Disabled Students Program (PDSP) at Berkeley, a program with three main parts: a pool of attendants and emergency attendants for people; a group of engineers who would repair wheelchairs; and, eventually, an accessible housing list. The PDSP was so successful that, much to the chagrin of the university, people in the community began to use its resources.

Out of this kernel of an idea grew the Berkeley Center For Independent Living (CIL), a revolutionary concept at the time, it was a fledgling organization intended to provide the vision and resources necessary to get disabled people out into the community.

In Ed’s words, “The Berkeley CIL was also revolutionary as a model for advocacy-based organizations. No longer would we tolerate being spoken for. Our bylaws said that at least 51% of the staff and Board had to be people with disabilities, or it would be the same old oppression. We also saw the CIL as a model for joining all the splintered factions of different disability organizations. All types of people used and worked in our Center. This was the vision we had for the future of the movement.”

Berkeley CIL would be the first and would lead to a network of similar organizations across the country and around the world- including The Ability Center. Ed would go on to be awarded a MacArthur Grant for his efforts, to marry, raise a son, and lead a movement that resulted in the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, and other disability rights law that lives on today.

We as an organization and as individuals living with disabilities owe a great debt to Ed Roberts and his inability to say no to those who would hold him back. His vision and efforts, along with the vision and efforts of his contemporaries, and those who followed in his wheel tracks, has made our world a far better and more accessible one.

For all of this, we celebrate his birthday and his life on this January 23.