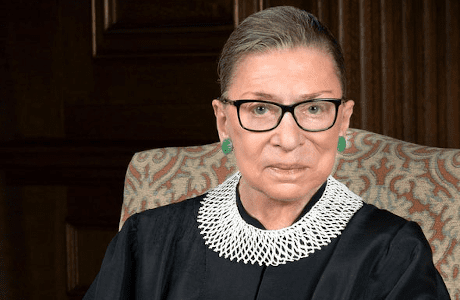

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was famously a brilliant advocate for gender equality while she was a practicing attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union. Less popularly known is her lasting impact on the rights of people with disabilities as a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. People with disabilities have struggled to get U.S. Courts to recognize and enforce disability rights. In 1927, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes upheld the right of states to involuntarily sterilize people with disabilities who were residents of institutions in Buck v. Bell. The first court cases brought under the ADA in the early 90s and 2000s were often dismissed. Justice Ginsburg saw things differently.

In Tennessee v. Lane, Justice Ginsburg wrote that by passing the ADA, Congress finally included, “individuals with disabilities among people who count in composing, ‘We the People.’” Her analysis in Lane, dealing with access to the court system, foreshadowed her majority opinion in Olmstead v. L.C., arguably the most important disability rights case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The opinion, written by Justice Ginsburg, decided that, “undue institutionalization qualifies as discrimination ‘by reason of . . . disability’.” It held that states must have a comprehensively working plan for moving people with disabilities into less restrictive settings. For a country that traditionally has enforced laws requiring involuntary institutionalization, Olmstead has been labeled the Brown v. Board of Education for people with disabilities. Since the decision, over 80 lawsuits and DOJ investigations in more than 25 states have used Olmstead to ensure that people with disabilities are able to live in the community rather than be shut away in institutions.

Justice Ginsburg understood that, “Institutional placement of persons who can handle and benefit from community settings perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life,” and, “institutional confinement severely diminishes individuals everyday life activities.” Her judicial legacy lays the groundwork for the dignified and equal treatment of people with disabilities under U.S. law.